This article first appeared on Arutz Sheva

Israel National News – Arutz Sheva travelled to Southern Israel with Regavim to witness up close what many call “loss of governance in the Negev,” and to find out whether construction of the three communities the government is planning for the Bedouins will solve the problem or make it worse.

“We must understand that this is a national issue – there is an illegal community spread out over hundreds of thousands of dunams, and the State of Israel should be looking decades into the future, not only at the here and now,” says Avraham Binyamin, Head of Policy, Regavim.

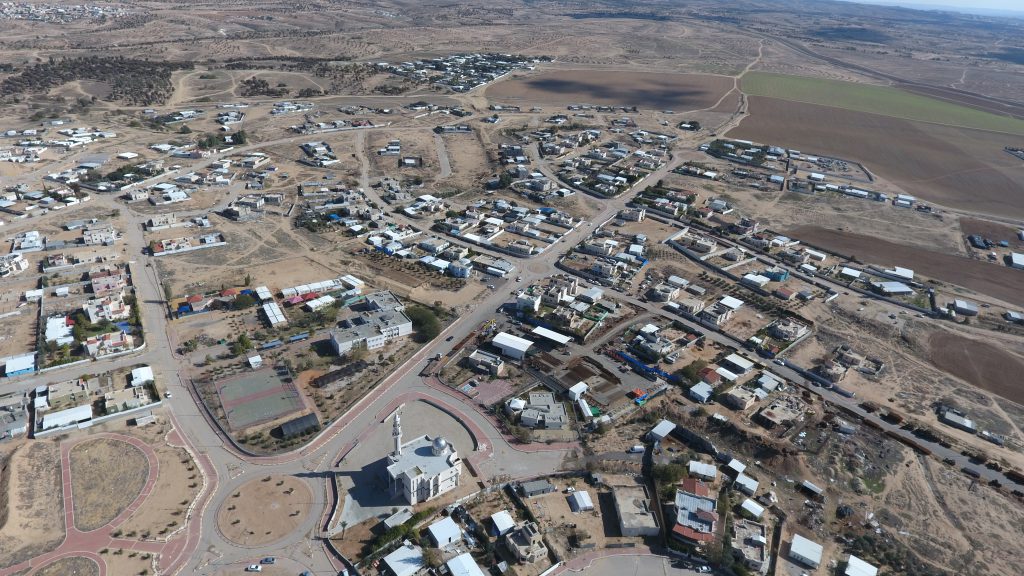

Looking at the ground from an aerial view, there is a clear picture of the dispersed tents and the villages.

“You can see it’s a huge swath of land, everything you see is illegal,” says Evyatar David, Regavim Southern Region Field Coordinator. “There is a tremendous amount of squatters on a vast stretch of land. No planning, no regulation, and no solution from the government for this matter.”

Israel has tried to create a solution for the Bedouins in the past, and in the late 1960s, it established cities for the Bedouin population to provide an adequate response to their needs. But, according to Regavim, that didn’t really work.

“Between 1966 and 1970, the State established seven cities, in the Bedouin area – within the ‘Sayeg’ Triangle, and told the Bedouins, come live in the cities we’ve built for you,” David says. “The Bedouins refused to enter, because under Bedouin law and Bedouin practice, if the father, grandfather and son used a particular piece of land, that land belongs to them.”

Meir Deutsch, CEO, Regavim, explains that the urban construction plan created by the State of Israel for construction of residential units can house 35,000 residents.

“In actuality, there are 12,000 residents living in Lakiya today. Why? Because most of the land in Lakiya is under claim of ownership,” Deutsch says. “The only person who decides what happens in claimed land is the person claiming it. No one else can decide what happens with that land, not the court, not the police.”

He adds: “The only homes you do see are those of people claiming ownership. Either the person claiming ownership, or their children or someone they sold to.”

These claims are far beyond logistic or legal issues. The war over ownership can escalate into violence and murder.

“Almost half the Bedouin population still live in scattered clusters, and the government wants them to consolidate within the villages and cities,” Deutsch explains. “But the Bedouin says: I can’t come live here, I will be killed.”

David notes that nobody comes in to the seven cities established for the Bedouins “because there’s an ownership claim, from a clan claiming that this land belongs to it.”

“Anyone who comes here will be shot in the head. So the government provided a solution that is irrelevant and inapplicable,” he says.

The result is that land allocated by the government, and prepared for residential construction, is empty.

“We can see the spread, and the empty fields, which are actually pieces of land on which there are claims of ownership,” David says.

He points to a neighborhood built by the government for the Bedouin community – “but it too is under claim, so no one goes to live there.”

There is an entire neighborhood in Lakiya that was developed.

David explains: “There are plots ready for construction, pillars, electricity and water, but no one will come because there is a claim of ownership. A person or family or Bedouin clan who claim the land belongs to them, and nobody can live here. Because whenever it is their land, no matter what the government says and the State claims, or what the government develops, ultimately the rules of the south are what matter.”

Other than residential issues and the takeover of the land in the Negev, Regavim also warn of internal processes that are unfolding within the Bedouin population. They emphasize that the government is unaware of the situation on the ground, and there is no law or justice at the moment.

“There are two components of Palestinization that are gaining momentum within Bedouin society,” Binyamin says. “One is related to polygamy, with women who are imported, there is trafficking of women coming in from the Gaza strip and from Judea and Samaria, and in fact we have dozens of percentages of Palestinian women and their offspring in the Negev Bedouin society, and that inevitably affects the values that society absorbs. The security services also tell us that the majority of Bedouin citizens involved in terrorist attacks are those connected to Bedouins from Judea and Samaria or Gaza, through these second and third wives.”

He adds: “In addition, Bedouin society has also been infiltrated and influenced by the Islamic Movement, the southern stream, which is connected to Ra’am, as well as the Northern, with teachers coming from the northern stream, which has already been declared illegal, teaching and imbibing these values.”

Noting that Bedouin society used to be a society of nomads, Binyamin says that it is “becoming increasingly nationalistic and Palestinianized, and that is also manifest in the huge decline in enlistment numbers, which today are negligible, nearly nonexistent.”

As Israel National News – Arutz Sheva reported, the government approved the construction of three Bedouin villages. According to the decision, the villages will be built only if 70 percent of the scattered Bedouin communities commit to leaving the land on which they are squatting and moving into them.

Noting that Bedouin society used to be a society of nomads, Binyamin says that it is “becoming increasingly nationalistic and Palestinianized, and that is also manifest in the huge decline in enlistment numbers, which today are negligible, nearly nonexistent.”

As Israel National News – Arutz Sheva reported, the government approved the construction of three Bedouin villages. According to the decision, the villages will be built only if 70 percent of the scattered Bedouin communities commit to leaving the land on which they are squatting and moving into them.

Regavim supports this decision, but demands that past mistakes not be repeated.

“We can build the villages, that’s fine, it’s the right thing to build them, provided the land the squatters are on goes back to the government in the end,” Deutsch says.

The problem, according to Deutsch, is how to include this stipulation as a condition in the government’s decision.

“We have to identify the entire population that is supposed to relocate into each village. We have to clearly define the size of the new town, where it will be, how large. We have to get the agreement of the citizens in the scattered Bedouin communities. Before they are a licensed town, they have to sign, 70 percent of them have to sign on their commitment to relocate to the permanent village. Naturally, there will be a small percentage that won’t, and the state will have to force them to relocate, and clearly in such a situation where the majority, 80 or even 70 percent come willingly, the government can handle the remaining 30 percent.”

He explains that establishing the three villages is “not the ideal situation.”

“The ideal situation is a map of the Negev for fifty years from now, that defines where the international airport is and where the trains go, where there are highways and cities and agriculture, and open areas,” Deutsch says. “Once you have that, you can decide where the Bedouin villages will be 50 years from now, and based on that, determine where to establish new communities now.”

While he says that “I don’t trust this government simply because it’s hard to trust someone who’s broken a promise,” he is willing to wait and judge them by their results.

“This government has asked us to judge them by actions, not words, so we will be judging them on that,” he says.

Regavim is publishing a book called “Bedouistan.”

“It reflects what we’d like to share with every citizen of Israel: Right under our noses, there’s a state within a state growing in the Negev,” Binyamin says. “We also point out the major problematic incidents that have plagued the Negev, which we find out about sporadically. We illustrate the problems and flaws in national planning over the years, as the State attempted to solve the problems, and of course we present our vision for the future, because ultimately, without a vision, there is anarchy, and we try to address this larger need, in order to solve the problems of the Negev.”